I have written before about a stunt carried out by the engineering faculty where I was a student. Protesting the amount of money paid by the university to provide public art, the engineers surreptitiously planted their own chicken wire and concrete “art”, waited until the student body was acclimated to it and then publicly demolished it in protest. The Arts faculty went berserk. The Board of Governors met in late night sessions. What to do about the willful vandalism of the engineers? When it was demonstrated that the “art” was homemade, there was egg on a great many faces. The prank played off ancient questions, “What is beauty? What is art? Does art need to be beautiful?”

As much as I am intrigued by these questions, I recognize that I am likely the last person qualified to opine on the topic. I am wedded to the concept that “close enough is good enough”. A successful saw cut need only be in the vicinity of the line and if errant hammer blows dent the wood, well that is life. The tile floors that I have laid would tear off your toes if you tried to slide on them and if my stick men drawings include a bend at the elbows and knees then the representation is good enough. It is not clear to me that I would recognize beauty when I see it. Does this mean, then, that beauty is “in the eye of the beholder”? Or are some things objectively beautiful and not open to preference?

I once had the great pleasure of touring the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, Russia with a fellow consultant who owned an art gallery in South Africa.

“It will take longer than I would like but I will get a real lesson in art today!” I thought to myself.

Wrong. He moved through the endless rooms of great art with the same alacrity as I and when I questioned him on it he said something like,

“If you have seen one then you have seen them all.”

That might be my interpretation of what he said. Great art is lost on more than just me. My preference in the art we saw that day were the giant pictures of Medieval kitchens with grouse, pheasant, and herbs hanging from the rafters while a pack of hunting dogs sniffed around the floor beneath. I have forgotten the name of the 18th century artist, but I liked his bold colours.

Was this art beautiful? It didn’t hold a candle to the architecture of the Hermitage which took my breath away and caused me to sit in the great galleries until my neck was too crook to continue looking up. So, is that architectural beauty objective or just a preference?

Will artificial intelligence be able to produce art that is beautiful? It is not there yet in my view. It can certainly knock out a rabbit faster than me and one that looks objectively more like a rabbit than my attempts, but I have yet to see anything that is beautiful. The problem with AI, it seems to me, is that it can’t produce anything but combinations of the artwork that it was trained on. Is a copy of the Mona Lisa art? Can it be beautiful? Can it be transcendent? Will we someday pay to have a guided tour of the Metropolitan Museum of AI Art? I can’t be sure, but I am thinking not.

What is the connection between beauty and being human? Do dogs and cats have a sense of beauty? It seems unlikely that a species that spends most of its time with its noses buried in the bums of others of the species is much taken with the concept of beauty, but the question must be asked. If beauty is a uniquely human artifact than this opens a whole new line of questions that deal with the nature of God and the role of beauty in being made in His image. Words like “transcendence” become important.

Is beauty determined by worldview or is what is beautiful in one culture necessarily beautiful in another? I guess the Japanese see beauty in little trees because they are little. Do I see such bonsai plants as beautiful? I must think about that.

What about children; do they perceive beauty, or do they have to learn from their culture what is beautiful? If it must be learned, can it be considered transcendent?

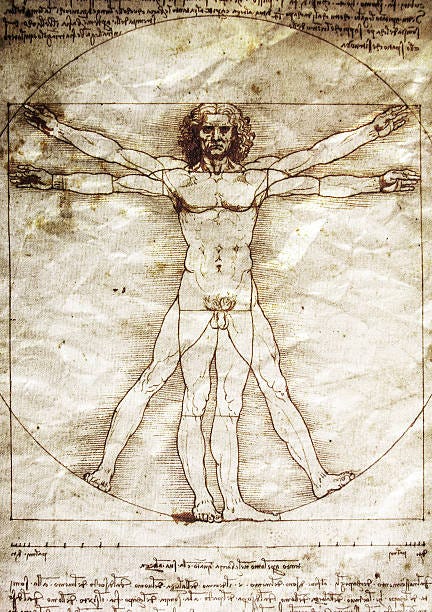

Some suggest that beauty is related to universal mathematical constants like the octaves of music, the relative dimensions of da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man or the Golden Ratio applied to the dimensions of the artistic object itself. In fact, there is a field of study called neuroesthetics which examines the mathematical relationships of beauty. These researchers look at measurable things like balance, proportion and symmetry to quantify beauty. It is unlikely that Helen of Troy, reputedly the most beautiful woman in history, had eyes which were not balanced on her face or a nose which dwarfed her ears.

The Bible is full of measurements that defined objects of utility such as the desert tabernacle, Noah’s ark, the first temple in Jerusalem and Ezekial’s temple to come. Is it safe to argue that God was not interested in the esthetics of such buildings and so we should not conclude that they were beautiful? Or are the measurements included to define that beauty? Does this mean that beauty can be quantified?

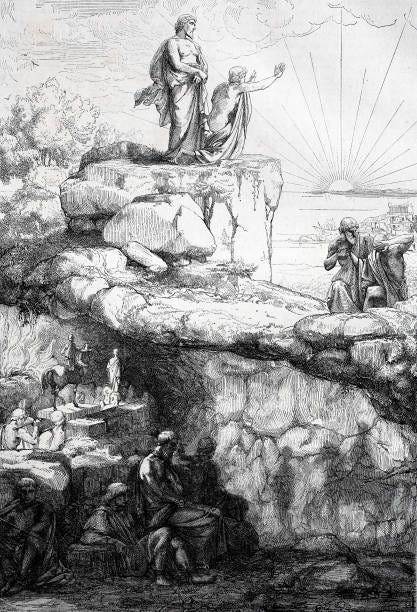

Socrates argued that there are three transcendentals: truth, goodness and beauty. Beauty is the lens through which we are to see and interpret truth and goodness. But until we define beauty, our lens is going to be fuzzy. Perhaps Socrates wanted it that way. His student Plato extended the definition. Plato defines true beauty as the contrast between the shadows flickering on the cave wall and the actual objects, the Forms, located outside the cave. We are chained inside the cave and can’t see the real beauty but can only catch glimpses in the shadows. According to Plato, it is only the unchained philosopher that can understand the beauty of the true Form.

Paul, in his ode to love in 1 Corinthians 13, uses a different metaphor to describe the same phenomenon,

“But now we see through a glass darkly.”

More importantly, Paul says that all humans can understand that beauty if only in glimpses. It is not reserved for Plato’s philosopher. Perhaps C.S. Lewis’ sharp pangs of joy are momentary flashes of recognition of the beauty of the true form.

I am not sure what to make of the stories of people who have died, gone to Heaven and then returned. There is lots of evidence for their deaths and their return from death. It is the bit in between that makes me scratch my head. But to the extent that I have followed these stories, when these people return from Heaven, they invariably speak of a beauty that cannot be expressed. Were they seeing the true forms?

Mike Rowe, in a recent interview with Sabin Howard, the sculptor of a remarkable war memorial, asked how Michaelangelo might have taken the news that he was awarded the job of painting the Sistine Chapel,

“Was it like Michaelangelo’s sphincters slammed shut?”

This begs the question of whether there is beauty in comedy? Coming from a family that places a high value on sarcastic humour, I have always been impressed by Jesus’ one liners. When Nathanael was invited by Philip to meet Jesus, he scoffingly said,

“Can any good thing come out of Nazareth?”

When Jesus subsequently saw Nathanael approaching, he got in the first word,

“Behold an Israelite indeed, in whom is no guile!”

Sorry Bible expositors, Jesus wasn’t commenting on Nathanael’s sterling character. He was having a sarcastic go at him for the snotty comment about Nazarenes. The really funny part is that Nathanael didn’t get the joke until Jesus explained that he saw him under the fig tree. I think Nathanael thought to himself,

“oh oh… he heard me taking a shot at Nazarenes.”

It was a complex joke and a very good one. I see a lot of beauty in it but maybe that is just my preference rather than objective reality.

What about literature? Is Dostoyevsky a better writer than Danielle Steele or Ayn Rand? Is The Plague by Camus the masterpiece that many suggest? The Gulag Archipelago is about as dark and pedantic and statistics-laden as any three-volume set of books can be, yet it completely changed my perception of the world. Does that, at least in part, define beauty?

Some argue that beauty is necessarily sacred and part of a divine order. We receive beauty (or in Plato’s view, its shadow) to redeem our pathetic, profane and often ugly world. It is an interesting concept but is it true? Based on the quality of the art produced, were the Italian and Dutch Renaissance periods a time of intense cultural redemption? If so, from what was the world being redeemed?

Flipping that around, are periods of bad art (like we currently seem to be in), reflections of discordance and nihilism? Did the bloodshed of the 20th century inure us to the opportunity for beauty? In the lee of enormous human suffering and horrible universal experience is it possible to see beauty? Or perhaps beauty is even more transcendent during such times.

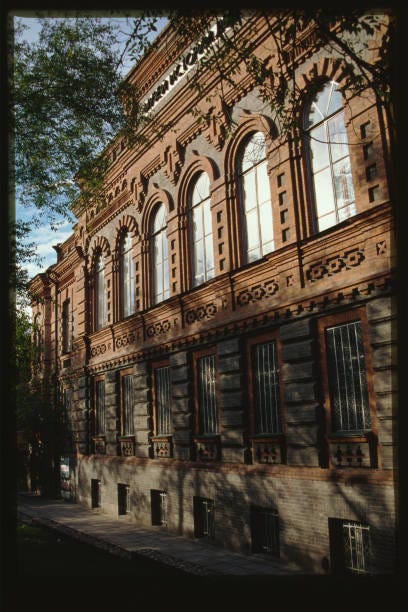

The most beautiful city that I visited in Russia was the eastern community of Khabarovsk. With the exception of St Petersburg, everywhere else was typified by the sterile ugliness of Soviet era apartments. Row upon row, block upon block, street after street of concrete bunkers with a broken swing set in an ugly playground. But not in Khabarovsk. When I offered the opinion that the city must have been designed and built in Tsarist times, I was told that Stalin was trained as an architect and Khabarovsk was his palette. I was stunned. What can that possibly mean? A sociopathic murderer is capable of producing such beauty?

Can there be beauty in ugliness? Can the pornography of consenting adults be beautiful? Was Hugh Hefner the artist he claimed to be? If the form of the human body is not beautiful in the context of pornography, can it ever be beautiful? The Renaissance painters seemed to think so. Again, I am not so sure. Does beauty need to obey boundaries?

Robert E Lee famously said,

“It is well that war is so terrible, or we would grow too fond of it.”

He made this comment from behind a defensive shelter as thousands of Union troops were being massacred at the Battle of Fredericksburg. The carnage did not prevent him from making a comment about the beauty implied in a well-fought battle. Well-fought, at least, from his perspective.

Canadian prisons are full of First Nations artists, and, looking at their artwork, I wondered how beauty can be found in prison. Some of the artwork that I saw was, to my undiscerning eye, objectively beautiful. Does this mean there is no relationship between beauty and freedom? Beauty is to be found where beauty is found and there are no externalities which influence its reality? Perhaps this is what transcendence means. Some would call this transgressive and argue that beauty can only exist where boundaries have been breached. I might argue that this is the cause of the increasing ugliness of our world.

Considering this paradox, many commenters point out that beauty is in the contrast. Contrast is the mother of clarity they argue. Jonathan Pageau said this in a conversation about beauty,

“For every laugh you need a tear.”

Does this combination of ugliness with contrast mean that the crucifixion is a beautiful event? It perfectly accorded with God’s will so was it beautiful? Was the crucifixion the necessary additive to justice to give it beauty? The wounded Jesus is not beautiful, but his wounded body is the object of more art than any scene in history. Is the ugliness of his wounds the contrast needed to demonstrate the beauty of our redemption?

Is beauty so sublime that it can only be truly appreciated at the deeper, spiritual level? If this is the case, then what of beauty that is less than deeply sublime. Is it faux beauty? Semi-beauty? Is there a scale of beauty? Must the decision be binary - either beautiful or ugly?

In a previously mentioned interview, Mike Rowe expressed a hesitation to use the adjective “divine” with the noun “art” and I wondered why he would have this hesitation.

I have peppered you with questions without answers mostly because it is not clear to me that there are answers. But I was a member of the faculty that put out fake art to embarrass the fake artists; who used unsanctioned ugliness to expose sanctioned ugliness. Therefore, I am going to venture an answer to the question with no attempt to convince you that I am right,

“What is beauty?”

In my gradually forming view, beauty can only be assessed in the context of a referent. Ultimately the beauty of what you suspect is beautiful can only be assessed in relation to something that is objectively beautiful. You need a point of reference, and the question of beauty is really a question about the reference point being used. If we get the reference point wrong, then beauty becomes ephemeral and meaningless.

I also think that beauty is a matter of preference based on the personality and worldview of the individual human making the assessment. We are all different and so we are each going to see beauty in different “modalities” to use a meaningless bit of jargon. Let me explain.

A company once owned land in the river valley below the plateau on which I live. They used their land to crush and screen river rock for local construction projects. Starting as a young boy, I have always loved to watch construction equipment, and I have a special spot in my heart for screening plants. I don’t expect anyone to understand this, but it is what it is. For probably twenty years there was an ongoing battle between the construction company and the city. There were public meetings organized to kick the owners off their land or demand that they donate the land for public use. I dutifully went to the meetings and suggested that this was not a universal sentiment because I loved sitting on the embankment to watch the operation. My comments always elicited groans from the rest of the audience. Who cares. Beauty is where beauty is.

The company finally got a reasonable offer for the land, and it was turned into a “polishing pond” for storm water runoff. That is, it is a swamp full of bullrushes and an attractor of many bird species. There are people who see great beauty in this and stand along the swamp banks for hours looking through binoculars. To them it is beautiful, but I lament the loss of the screening plant. Is one of us wrong? I don’t think so.

So, there is a particularity to beauty that is highly personal, but it must still be measured against a reference marker. I believe the reference marker must be transcendent and is deeply anchored in the sacred. No, Mike Rowe, you are not wrong to use the word “divinity” in a discussion of beauty because the reference point we need to use is attached to the divine.

God is love we are told, and I believe the assertion. So there can not be beauty in hate. Ever. Real beauty involves an attempt to distill symbolically or directly some element of God’s love. Joyce Kilmer addressed this in his poem about trees,

“I think that I shall never see, a poem as lovely as a tree.”

Was the poem an expression of beauty or was it the tree, as the object of the poem, that was beautiful? To Kilmer, the tree was beautiful, and he wasn’t specific about a particular tree. The poem was his symbolic attempt to glorify that beauty. But where does the tree come from? It is part of God’s creation, and we haven’t begun to plumb the mysteries of photosynthesis. That mystery is what, in my mind, is ultimately beautiful. The beauty of the tree is the siren song to draw us into the mystery. I think it was this mystery that caused Plato to speak of forms not seeable while chained in the cave.

I think the reference point of beauty, then, is not the siren songs or symbols but the degree to which the symbols draw us into the mystery. The Maker of the mystery is the ultimate guidepost to beauty but His beauty is not directly knowable and so we have to make do with proxies; mysteries and symbols of the mysteries.

In my mind, anything that draws us toward the mystery, and thus toward God Himself, is a candidate for beauty. It can be a mathematical equation, E = mc2, for example. People spend their lives pondering the significance of that equation. Are they willing to invest this time and effort in the pursuit of the ugly? I think not.

Other people spend their lives studying human anatomy to capture, symbolically, the essence of bones or a muscle group because these are the things that give shape and meaning to the other humans around us. They seek to answer questions shrouded in mystery and their artistic attempts can be strikingly beautiful.

Other people I know are willing to give up sleep to shiver on a hillside and watch a sunrise or will spend considerable time and money to photograph sunsets. Is it the interplay of celestial colours that is beautiful, or are the mysteries shrouded in the physics of light diffraction beautiful?

We are drawn to mystery because we intuitively believe that in the mystery we will encounter God, the Maker of mystery and the source of Beauty. That is why Christians venerate a wooden cross. It is full of mystery that is directly connected to the Maker of mystery.

Why are we attracted to the Maker of mystery? I think it is because we are made in His image and, as children seek to know their image-giving parents, we seek to know Him whose image we bear. That is why beauty is understood universally. Image bearing doesn’t stop at political boundaries.

Finally, does this mean that denial of the mystery is the opposite of beauty? Is ugliness a logical consequence of ignoring God? I once had a conversation about the Orthodox faith of Russian citizens in the 21st century. I asked my Russian friend about the obvious interest Russians have in Christianity and devotion to the Orthodox church.

“Yes,” he said, ”in Russia everyone goes to church.”

I have heard that said about North American spirituality prior to the 1960s so I doubted him and asked,

“Really? Everyone goes to church every week? 100% of people go to church?”

“Yes, really. Everyone goes to church every week that they are able.”

My Russian friend had lived in Canada and was the holder of a PhD in geology. Trust me, no other geologist I have ever talked to would suggest that 100% of any group of people go to church every week. Still doubting and, granting for the moment that his assertion was correct, I asked why everyone would go to church. His response was revealing,

“Because for over 70 years we were not allowed to go to church, and many lost their lives because of their faith. We understand the violence and ugliness of a world without God, and we don’t ever want to return to that. You Canadians might be wise to learn from our mistake.”

It is a sobering thought. Perhaps our world is getting uglier because we are moving away from the Maker of mystery and the source of all Beauty. When we seek to demystify the world around us by living exclusively in cities we will live in ugliness. If we seek to demystify by pretending that our world can be artificially created by drugs or computer programs, we will live in ugliness. If we seek to demystify by arguing that science has destroyed faith, we will live in ugliness. Can we not recognize that science is actually the daughter of faith? When we proudly proclaim that God is dead then we will relive the 20th century and live in ugliness. Fortunately most people in the world are not as fatuously arrogant as we in the west so the spread of ugliness will be limited.

I hope you will chime in with your own thoughts.

Speaking of Reality Truth and The Beautiful too not much of these three inter-related (even circular) themes can or will be found in anything associated with Donald Trump who is of course a pathological liar and a life long grifter con-man.

He is also a completely Godless religiously and culturally illiterate nihilistic barbarian.

There will of course be a complete absence of Truth and especially The Beautiful Itself in the Orange Monstrosity new toxic-all-the-way-down-the-line administration. The Orange Monstrosity is sometimes referred to as Orange Jesus

First, I have to thank Lytle for wrestling with a subject that rarely sees the light of day. Reading "Let my heart be still" was an experience in recognizing his questions as much like ones I myself have had, and then struggling, like Lytle, to find the answers. One of my first thoughts is kind of a non sequitur, I once heard a wise man say, "People often say, 'I don't know much about art (read beauty), but I know what I like. But in fact, they like what they know.'" There's more than a little truth to that, but I'm not sure it explains anything. One aspect of Lytle's subject that has always fascinated me is the portability of beauty. He spoke of bonsai plants and snidely remarked the Japanese must like them because they, like the plants, are small. Well, the Japanese are not universally small. And I'm not small, yet I adore bonsai, as do many other Europeans, some of them much larger than me. Actually, I don't think size has anything at all to do with appreciation of Bonsai. It is popular worldwide because in one single living object it can evoke the beauty of an entire forest, and it can do this in one's living space. I think there are clues in this. True beauty is universal because, in one way or another it is always a reflection of God, Who alone is the source of truth, goodness, and beauty. Don't forget, all of us are made in the image of God, which means we are predisposed to appreciate beauty from God's perspective (not perfectly, we are all sinners, yet all of us still possess a surprisingly large remnant of the divine) and it is the imago dei, still present and still operative, that prevents our world from descending into total chaos and ugliness. The devil has had to work hard to replace beauty with ugliness, and in a few places he has succeeded. But you can always tell that he has suffered ultimate defeat in that his attempts never quite succeed. The Soviet Union collapsed and people did go back to church to worship in beautiful orthodox cathedrals. And that always happens. I'm not a prophet, and therefore cannot say when, but I know beyond the shadow of a doubt that the ugliness of present North American life will someday be replaced by the beauty of lives lived in fear of God. Well done, Lytle, well done.